By Rabbi Judah Mischel – Jewish Action

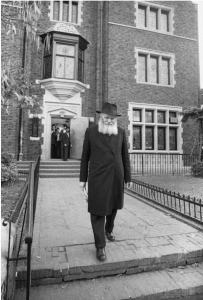

Like many of our neighbors growing up in Monsey, we had a large finished basement where we watched sports and hung out. I didn’t think there was anything out of the ordinary about our home decor. Yet amid the typical fare of Israel-oriented Judaic art, a striking black-and-white poster of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, hung prominently. Though we were not Lubavitch in any formal sense (we affiliated with Centrist, Religious Zionist institutions, schools and shuls), the poster was a testament to my parents’ initial exposure to Torah observance through Chabad shluchim at the University of Buffalo. The Rebbe played a formative role at a critical juncture in my parents’ lives, and in our development as a family.

Gimmel Tammuz marked twenty-five years since the Rebbe’s passing, offering an opportunity to consider how the Rebbe’s worldview and accomplishments can impact and inspire our lives today.

The Rebbe was larger than life; he was a tzaddik, gadol baTorah, commander in chief, nasi, revolutionary, spiritual entrepreneur, CEO, father figure and zeidy. An indefatigable leader who was loving and supportive and demanded incessant growth, he consciously and deliberately cultivated leaders, not followers. The Rebbe encouraged independence and inspired confidence.

To a college student who asked what a Rebbe’s job is, the Rebbe responded by quoting his father-in-law, the “Frierdiker” (previous) Lubavitcher Rebbe: “There are many treasures embedded in the earth—gold, silver and diamonds—but if you don’t know where to dig, you’ll just hit rocks, mud and dirt. A Rebbe is a geologist of the soul; he can tell you what to dig for and point you in the direction of where to dig for it . . . but the actual digging you must do for yourself.”

The Rebbe had deep faith in the greatness of nishmas Yisrael, and focused efforts toward enabling every man, woman and child in Klal Yisrael to engage deeply in a meaningful Jewish life and to unearth his or her own treasures. When most leaders and rabbis turned away from a generation of rebellious youth, the Rebbe turned directly toward the deepest part of the souls of this generation and asked them to reveal their innate diamonds.

The Rebbe rejected the notion of kiruv; labeling other Jews as far away is presumptuous and judgmental. Every Jew is already close to Hashem. Likewise, the Rebbe disapproved of implying that there are those who have no Jewish background. All of us are equally descendants of the same Avos and Imahos, and they are our background.

As a young man, Shabtai Slavaticki, a student at the Kol Torah yeshivah in Jerusalem, accompanied his rosh yeshivah, Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach, the posek hador, to the Kosel to daven. There they saw a line of men waiting to lay tefillin at a Chabad stand and Rav Shlomo Zalman remarked, “People think the Lubavitcher Rebbe is a great believer in God. It is clear to me that the Rebbe’s greatness is that he believes in Jews!” Rav Shabtai later studied at Lubavitch Headquarters (known as “770”) in Brooklyn’s Crown Heights neighborhood and eventually became the head shaliach in Belgium.

The Rebbe’s faith in Klal Yisrael and his empowering message are relevant today more than ever: the treasure we are to dig for is within ourselves, and it is also found in assisting others in their process of spiritual self-excavation. In the words of the Rebbe’s predecessor, the Baal haTanya, the essence of every Jew is a Nefesh Elokis, a Divine soul, which is ultimately part of God above; a “cheilek Elokah mima’al, mamash” (a portion of the Divine, literally). Infinite Divinity is manifest in every Jew. Thus, every individual, with all of his or her unique strengths and talents, is critically important. Every action, mitzvah, consecrated moment, sacred movement and effort has unimaginable, infinite consequences.

“The Rebbe’s greatness is that he believes in Jews!” Indeed, the Rebbe believed in and encouraged each person k’darko, exactly where he or she is. He challenged artists to spread the light of Torah through their art, journalists through their writing, engineers through their designs and parents through raising a family. Every one of us shines with our own unique God-given abilities and strengths.

The Rebbe’s spiritually radical model of “Mitzvah Campaigns” still challenges members of our community to step out of their comfort zone and share their knowledge, opportunities and blessings with others. From asking men on the street to lay tefillin and women to light Shabbos candles to hosting massive Lag b’Omer parades and public menorah lightings, the Rebbe made it his mission, and every Jew’s mission, to reach out and reveal the treasure of every Yiddishe neshamah.

Additionally, our own commitment to and enthusiasm for mitzvos are strengthened when we share them with others; our emunah is amplified when we invite others to join us in participating in observance. And every mitzvah, every word of Torah we learn, every penny we put in the pushka, each good deed done even momentarily by the simplest, least-educated Jew brings us all closer to our ultimate fulfillment.

Even one of the Rebbe’s most vocal ideological opponents, Rabbi Yoel Teitelbaum, the Satmar Rebbe, is reported to have complimented the Rebbe’s Mitzvah Campaign initiative: “When a shaliach asks a passer-by if he or she is Jewish, this compels the Yid to affirm his Jewish identity, awakening connection and touching the spark within.” The mere recognition that one is Jewish can reignite the candle flame of one’s soul, spreading light throughout the universe.

The Rebbe referred to this mission as “Gaon Yaakov”—the restoration of authentic Jewish pride based on a return to Jewish identity, practice, values, ritual and tradition. The Rebbe assumed the mantle of leadership in the shadow of the Holocaust and breathed new life, hope and confidence into a broken nation emerging from darkness and the brink of decimation.

The Rebbe’s imprint is felt worldwide, most prominently perhaps in Eretz Yisrael. For over fifty years, every major Israeli political and military leader maintained a relationship with the Rebbe, directly encouraged the value of “Gaon Yaakov,” and helped to manifest it geopolitically as a national sense of self-respect, empowerment and pride.

Across the globe, public expressions of Jewish life and symbols serve as a celebration of Yiddishkeit without compromise, and openly encourage the most natural way for a Jew to express his or her identity: by “doing Jewish.”

As a teenager, my parents encouraged us kids to “do Jewish” by being involved in community service on behalf of Klal Yisrael. Although my parents never had the opportunity to learn formally in Jewish institutions, their commitment enabled us to have that zechus. The Yiddishkeit of our home was intuitive, experiential and growth-oriented. It fostered a sense of responsibility to our People and a natural connection to Jewish symbols, culture and books. Classic works such as Wouk’s This is My God, Elie Weisel’s Souls on Fire and The Fifth Son, and Menachem Begin’s The Revolt fanned the flames of our “Gaon Yaakov,” building our faith in Jewish self-determination and identity. Not surprisingly, years later, I discovered that each of these authors had his own special, close relationship with the Rebbe, each one drawing inspiration, direction, guidance and strength from him.

Beyond their warm personal relationship, Rav Yosef Dov Soloveitchik credited the Lubavitcher Rebbe with playing a significant role in “rejuvenating Judaism in America” by unapologetically representing traditional Orthodox Judaism and Torah values in the public sphere. After attending a farbrengen in 1981, the Rav remarked: “Er is a gaon, er iz a gadol, er iz a manhig b’Yisrael, He is a genius, he is a great man, he is a leader of the Jewish people.”

As a “leader of the Jewish people,” the Rebbe’s gadlus and remarkable impact were in no way limited to his own specific Chabad constituency. Rather, he effectively shaped the context in which thousands, if not millions, of Jews and gentiles in our generation relate to every area of Jewish life and practice, including mitzvah observance, education, public policy and engagement of the broader Jewish community.

In the most positive, empowering way, the Rebbe also insisted that we “do whatever we can,” not only in our own limmud HaTorah and shemiras hamitzvos, but in lovingly sharing the flame of Yiddishkeit to illuminate others. In encouraging those “who know alef to teach alef,” the Rebbe charged us to do our utmost to provide for the material and spiritual wellbeing of our brothers and sisters.

As Rav Adin Steinsaltz has pointed out, it is incongruous to speak of the Rebbe’s legacy. What the Rebbe left are marching orders. Beyond all the hundreds of volumes of Torah thought, speeches and letters, and thousands of hours of recorded sichos and meetings, the Rebbe left a task to be completed. The ideas and the content are simply resources to provide the understanding that will enable us to carry it out.

Our family’s narrative is only one among countless stories. But beyond all of the individual accounts of inspiration and growth, we must pause and contemplate how the Rebbe’s marching orders can positively impact our community going forward. In honor of the Rebbe, a quarter-century after his passing, let us ask ourselves some challenging questions:

What lessons can our Centrist community draw from the Rebbe’s doctrine of selflessness, and commitment to taking responsibility for the wellbeing of other Jews no matter what their denomination?

Am I personally using my God-given abilities and blessings for the betterment of those around me and increasing awareness of the Ribbono Shel Olam in my day-to-day interactions?

In what ways can we apply the Rebbe’s belief in Jews to our own relationships, and cultivate welcoming, spiritually positive environments in our homes, schools and shuls?

How can I unearth and reveal the diamond in every Jew and transmit the ruach of “Gaon Yaakov”— Jewish pride in Torah and mitzvah observance—to the next generation?

Have I done all that I can to prepare for the coming Geulah?

My parents’ poster of the Rebbe now hangs in my home in Eretz Yisrael, a constant reminder of how against all statistical odds, because of the Rebbe’s vision and my parents’ courage and sacrifices, our family is fortunate to live an engaged Jewish life. It is also a reminder of the commitment of the Rebbe’s shluchim, and the responsibility that rests on us to pay these gifts forward.

Rabbi Judah Mischel is mashpia of National and New York NCSY, executive director of Camp HASC and founder of Tzama Nafshi. He lives in Ramat Beit Shemesh with his wife, Ora, and their family.

This article was featured in Jewish Action Fall 2019.

Discussion

In keeping in line with the Rabbonim's policies for websites, we do not allow comments. However, our Rabbonim have approved of including input on articles of substance (Torah, history, memories etc.)

We appreciate your feedback. If you have any additional information to contribute to this article, it will be added below.